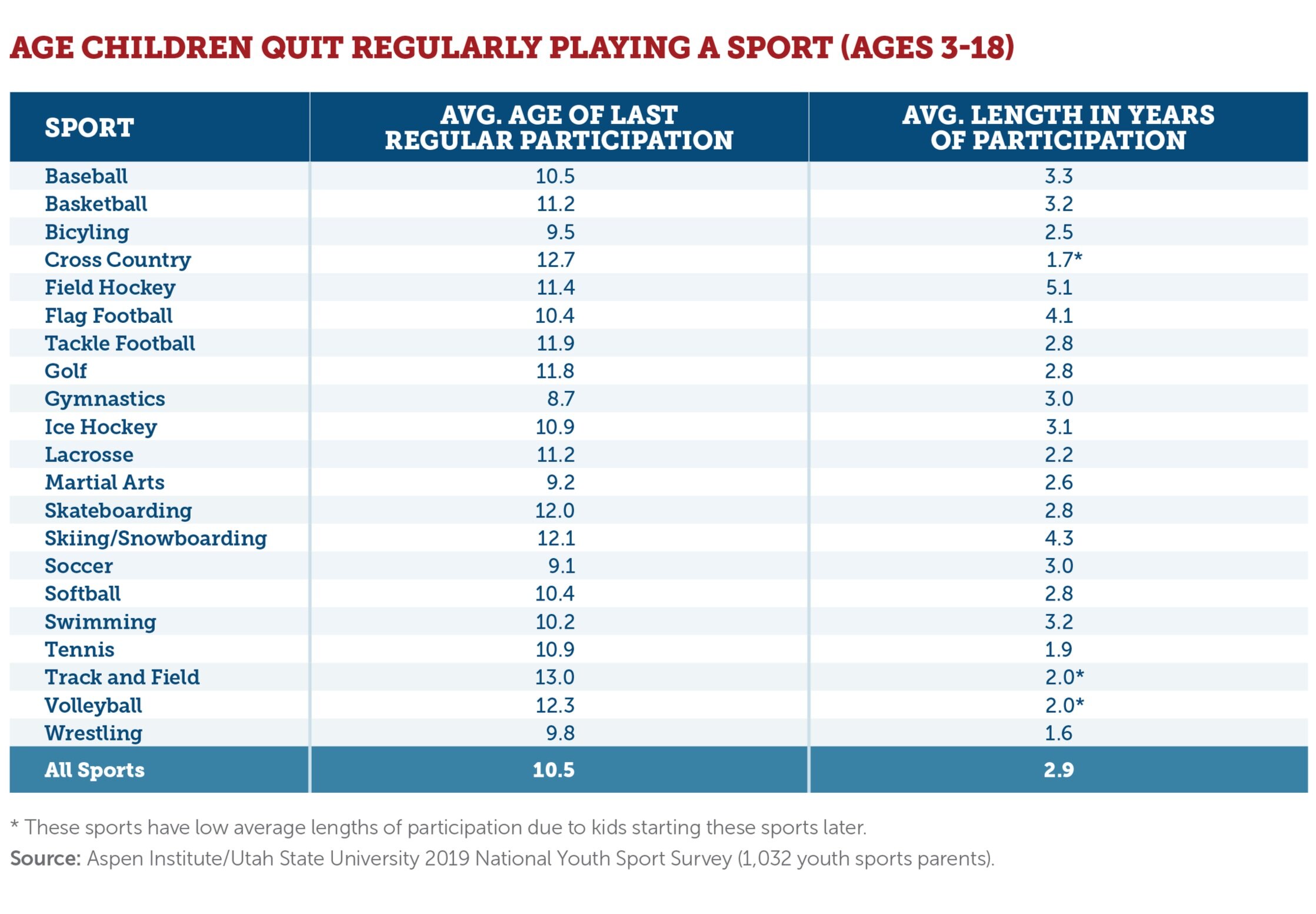

The average child today spends less than three years playing a sport, quitting by age 11, most often because the sport just isn’t fun anymore. Their parents are under pressure, too, with some sports costing thousands of dollars a year and travel expenses taking up the largest chunk.

These are among the findings of a new national survey of parents of youth athletes conducted by the Aspen Institute with the Utah State University Families in Sports Lab. The results offer key insights on the contemporary challenges of getting and keeping kids involved in sports, the theme of a new public awareness campaign, “Don’t Retire, Kid”, that launches Aug. 4.

In 2018, only 38% of kids ages 6 to 12 played team sports on a regular basis, down from 45% in 2008, according to separate research from the Sports & Fitness Industry Association (SFIA). The National Youth Sport Survey, commissioned by Aspen through its Project Play initiative, digs deeper into the reasons why participation has declined, while extending the analysis of youth up to age 18 and at all competitive levels (recreational, club, high school). Among the survey’s key findings:

Above all, parents want sports to be fun for their children. They hope that participation will promote physical and emotional health, as well as sport skills, social skills and peer relationships, with each of those reasons rating above 4 on a scale of 1 to 5. But the most desired outcome, they say, is fun, which led the way at 4.49. At the same time, many parents are looking for extrinsic rewards as well – admissions advantages to colleges, athletic scholarships, and pro sports opportunities all scored above 3.

Parents believe their kids are having fun. They reported their children experience high levels of enjoyment from sports. But they also said most have at least a moderate level of stress, with field hockey and lacrosse scoring as the most stressful sports for kids. The least stressful were skiing/snowboarding, track and field, skateboarding and soccer. When asked to rate what sources their child feels pressure from in sports, parents pointed the most to coaches (3.37 average). For what it’s worth, parents say they apply less pressure than their child’s peers.

To keep them playing, many parents are willing to spend lots of money. Parents with a child in ice hockey spent on average $2,583 per year – the most expensive sport among the 21 sports evaluated. Other costly sports included skiing/snowboarding ($2,249), field hockey ($2,125), gymnastics ($1,580) and lacrosse ($1,289). The least-expensive sports: track and field ($191), flag football ($268), skateboarding ($380), cross country ($421), and basketball ($427). The average across sports was $693. But even the least-expensive sports had some parents spend in excess of $9,000 per year on one child. In six sports (baseball, gymnastics, ice hockey, skiing/snowboarding, swimming and tennis), some parents spent $12,000 or more in one year, with tennis at the highest end ($34,900).

Kids from lower-income homes participate less often. Our nationally representative survey, distributed by Qualtrics International, collected insights from 1,032 adults in all 50 states whose children played sports; parents whose kids did not play, or were forced to quit, were not sampled. The median household income of respondents was $70,000, slightly higher than the U.S. average of $61,937. The gap helps explain why children from low-income families are half as likely to play sports as kids from upper-incomes homes, according to separate research from SFIA. For these parents, even a few hundred dollars in fees can be hard to cover.

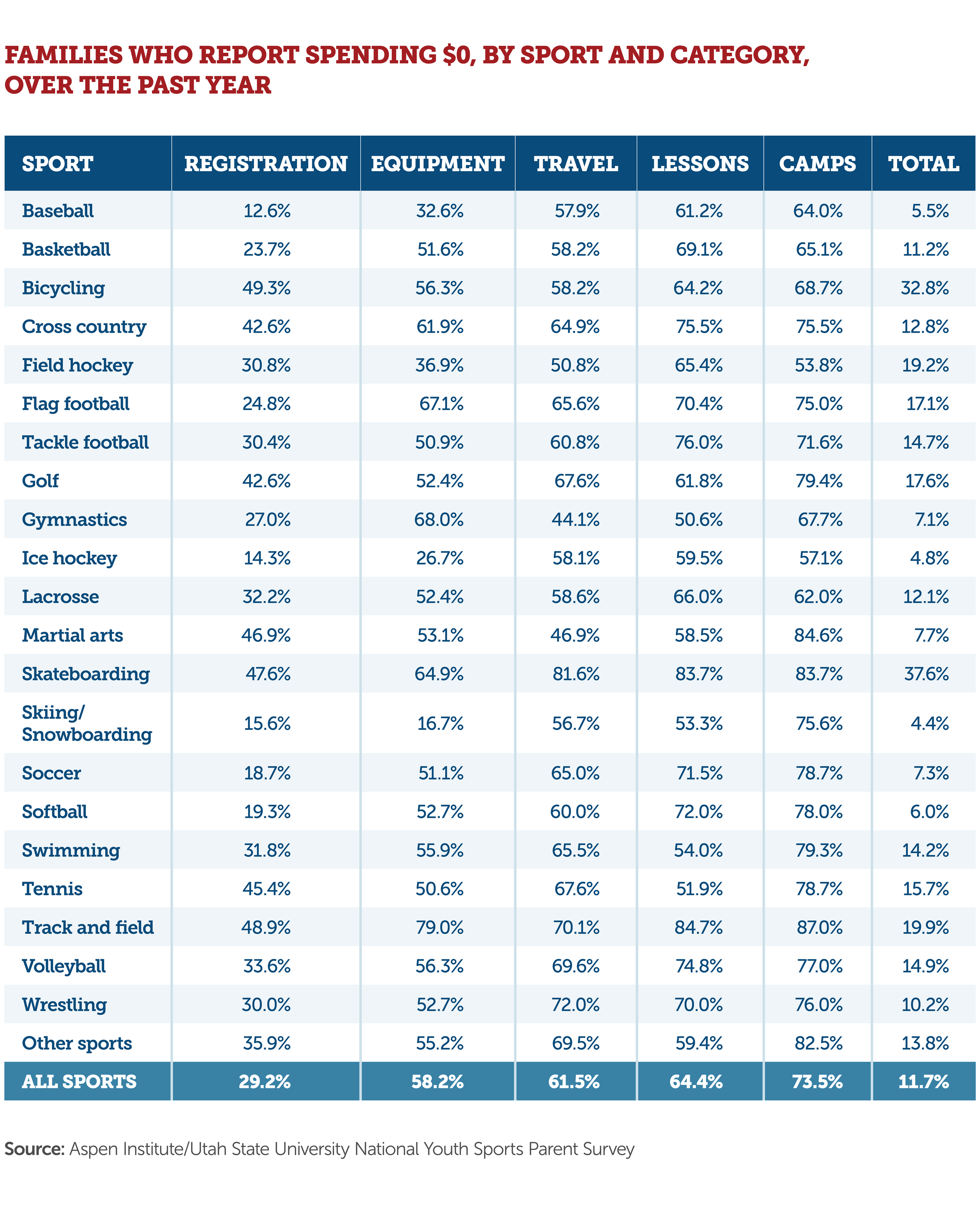

Recreational sports are free the most often, and there’s a large gap between traditional sports. On average across all sports, 12% of parents pay no money on their child’s sport, but there’s a huge sport-by-sport difference. Skateboarding (38%) and bicyling (33%) are the sports that are free the most. That intuitively makes sense given the nature of those sports. Among traditional pay-to-play sports, parents report far fewer free costs in ice hockey (5%), baseball (6%), softball (6%), soccer (7%) and gymnastics (7%). That’s two to three times lower in free costs than sports such as basketball, tennis, football, volleyball, golf, swimming and lacrosse.

Travel is now the costliest feature in youth sports. On average across all sports, parents spent more annually on travel ($196 per sport, per child) than equipment ($144), private lessons ($134), registration fees ($125), and camps ($81). That average includes all kids playing sports, not just those on travel teams, which often start in grade school and can cost families far more than a couple hundred dollars a year. Youth sports is now an estimated $17 billion industry, largely driven by travel teams.

See related charts at the bottom of this page for sport-by-sport comparisons.

The survey asked parents how often their oldest child regularly participates in sports – which the Aspen Institute defined as at least 35 practice, training or competition days within the previous 12-month period. One of the more comforting findings – at least for the parent who feels the pressure of what can seem like a runaway train – is the average age at which a child starts playing sports is still close to 8, despite some starting in preschool.

But kids also cycle out of sports quickly, discontinuing play after 2.86 years on average. This finding isn’t all bad, said Dr. Travis Dorsch, Utah State associate professor and founding director of the Families in Sport Lab, who designed the survey. As recognized by Project Play in its Sport for All, Play for Life playbook, sport sampling is healthy for children, and they can only try so many sports at a time, so if they move from one activity to another, that’s good.

“We need to figure out why they discontinue, not just that they do,” he said. “For kids, two years in a sport may seem like forever, while we as adults think they should continue for much longer. We need to frame it through the interpretive lens of adolescence.”

The key is that kids don’t move to the couch, so that they stay physically active. Most youth do not get the recommended levels of one hour of daily physical activity. Further, the new survey suggests that kids are rarely quitting sports so they can try other sports. Only 15% of the time that was the case, according to parents. Most often (36% of the time), their child just stopped enjoying or lost interest in a sport.

That’s a problem, with 45% of children today playing only one sport.

Among kids who do play, according to the survey, there is great variation in the level of commitment. The average child spent 11.9 hours per week on their sport, with the most popular sports – baseball (13.4), basketball (12.3) and soccer (10.8) – all around that mark. But some parents reported that their children play upwards of 60 hours a week during their sport season; that’s more than the average college athlete in any sport, according to NCAA research.

“I originally thought, ‘No way, parents are exaggerating,’” Dorsch said. “But there are probably gym rats or kids who spend the whole day at the park playing pickup games with friends with parents working in the summer who have nowhere to go and they’re playing 10 hours a day. I was one of those kids, so at the high end, I believe it.”

The concern is when coaches make excessive demands on kids, or sport programs push aside at an early age kids who are late-bloomers or whose families lack resources. “It’s a serious problem if at 8, 9, or 10 years old, kids are deciding or being told ‘this sport isn’t for you,’” Dorsch said.

And that can put parents in a tough spot, torn on how best to keep their kid in the game.

“For the parent who’s putting down $10,000 for their kid to play soccer, they see it as giving their kid every opportunity,” he said. “But the kid may feel, ‘Oh my gosh, they’re putting down $10,000 and now I feel pressure to perform.’”

Over the next year, Project Play will share and explore more findings from our national parent survey. Find free tools that can be used to get and keep kids involved in sports at our new Parent Resources page, created as a companion to the “Don’t Retire, Kid,” campaign. Sign up for our newsletter via the Parent Resources page.

Follow us on Twitter and Facebook as new analyses and resources are released. Do you have a question about youth sports? Send it to jon.solomon@aspeninstitute.org for consideration to publish in our monthly Project Play Parents Mailbag.